Willful blindness: addressing the epidemic of silence in organizations

When asked if there are issues at work that people are afraid to raise, a staggering 85% of employees say ‘yes’. Getting our staff to speak out has never been harder – or more important. How can we combat willful blindness in the workplace?

When the collapse of mortgage-backed securities triggered the global financial crisis in 2008, outrage and disbelief echoed around the world. How did nobody see it coming? How did it get this far? Why did no-one speak out, or stop it?

In the years and investigations that have followed, it’s clear that what was happening wasn’t hidden, unknowable, or unpreventable. The signs were there. People had access to the information: but they chose not to know.

‘Willful blindness’, former CEO, entrepreneur and author Margaret Heffernan explains, originated in law: but it exists all around us. At the simplest level, it’s information that you could know and should know, but choose not to.

It’s evident in epic disasters ranging from the systematic abuse within the Catholic church to the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill off the Gulf of Mexico. However, it also exists on small scales every day within our own organizations. Ignoring the obvious, Heffernan argues, is at our peril: it can have devastating effects. But combatting it is harder than many of us realize.

Why don’t we see what’s in front of us?

Willful blindness isn’t unique to any one organization, sector, or even country. It’s a human problem.

We’re selective in what we choose to know for many reasons.

Biologically, we have to have blind spots. We are inundated with information, every minute of every day: particularly in today’s digital knowledge economy. Seeing everything is, therefore, biologically impossible.

“We can’t notice and know everything: the cognitive limits of our brain simply won’t let us. That means we have to filter or edit what we take in.”

(Margaret Heffernan, Willful Blindness: Why We Ignore the Obvious at Our Peril.)

But what does get ‘filtered’ isn’t selected by chance.

We tend to blind ourselves to evidence or information that contradicts our existing beliefs. We are more receptible to what we already know: information that affirms our existing knowledge. In fact, people are twice as likely to seek out information that supports their own point of view as they are to consider an opposing idea. It’s the same premise that leads us to befriend and surround ourselves with like-minded people who share our ideals and belief systems.

More than that, we rationalize away contradictions. We use social justification, distance ourselves with impersonal data such as euphemisms or numbers, ignore the long-term consequences. It’s a phenomenon exemplified in the global climate change crisis, where willful blindness on an epic scale is fast-tracking the planet into an unrecoverable state.

This can be for any number of reasons: fear of repercussions, the unknown or what might happen; a desire to retain power, financial motivation, or perhaps the need for social acceptance or desire to conform. When there’s a problem, it might be too disturbing to consciously consider; or solving it may require extensive effort that we can’t contribute. It’s easier to brush things off than to speak out.

Silence in the workplace

In the context of an organization, willful blindness – and the silence that follows – goes even further.

For grass-roots employees, there’s often a belief that saying anything is futile, or perhaps ‘not my place’. In steep hierarchies, the problem is perpetuated. Those at the bottom feel they’re never going to be heard or nothing will change, as they don’t have power. So, what’s the point? By contrast, those at the top feel security from their position that they won’t be challenged or can act with impunity.

Sometimes, the ‘not my job’ mentality is the trigger. I see that the fire hydrant is broken in the staff kitchen, but that’s the job of whoever looks after health and safety. Surely if I’ve noticed, they’ve noticed: someone is already taking care of it. Reporting it would just be a waste of my time and theirs. I’ll be seen as a busybody.

‘Whistleblowing’ also historically doesn’t instil confidence in our staff to speak out. The fact of the matter is, when those responsible are called out – they tend to try and make the problem go away. Stories show us time and again the attempts to silence the whistleblower, to discredit them or even take steps to remove them from the organization.

(When Courtland Kelley sued General Motors in 2003 for not addressing safety issues affecting their vehicles, he believed he was doing the right thing. But not only did he lose his case, he was pushed out of his job: an outcome that made other inspectors fear speaking out. It wasn’t until 10 years later that the errors came to light. In the meantime, numerous people were killed as a result of the errors.)

Whistleblowers are regarded as troublemakers, stirring or invoking drama: attention seekers. Staff, then, are dubious or fearful of the unknown repercussions; it could come at a cost to their career or financial stability.

Or, the pack mentality offers a security blanket that we don’t want to give up. Perhaps I’m selling a product that I suspect is deficient or faulty – it could prove dangerous for the consumer. But I have my sales targets to hit and my bonus is dependent on achieving those. I’m part of a 20-strong team and we’re all selling the same product. If they’re carrying on, so should I. Why should it be up to me to speak out, to take the risk? Financial incentive is a powerful tool to get us to overlook moral sensibility.

Ultimately, employees are not motivated to publicly speak out against the status quo. This isn’t just about coming forward when something is fundamentally wrong: it’s a fear about contributing any idea or opinion that counters what the larger group thinks.

Those who think or feel differently won’t feel they fit in the organization, and may leave. This, in turn, breeds more of the same.

Willful blindness and silence among staff may not always led to a disaster: but it will prevent our organizations from innovating, changing, and reaching their potential.

Breaking the silence: how to combat willful blindness in the workplace

Willful blindness clearly comes at a cost. Ironically, strong organizational cultures can fuel the problem by creating an impetus for conformity among employees. The very same values that are supposed to drive performance in our organizations may actually be creating a cookie-cutter army of staff who bring to the table the same belief systems, assumptions and blind spots. Building organizations that overcome those limitations is to everyone’s benefit.

The question is, how?

#1: Hire people different from you.

Diversity in recruitment has been a hot topic in recent years, but while we’re beginning to recognize prejudice or bias in areas such as race, gender or disability, there is strong evidence that we continue to subconsciously hire people who affirm or align with our own mental models.

Surrounding ourselves with people who have different perspectives, experiences and arguments to bring to the table allows us to appreciate the limitations of our own. Addressing unconscious bias in the recruitment process needs to go further. Being aware of the problem is a positive starting point: but additional training to retain an open mind and bringing different scenarios or questions into the hiring process can help find those healthy differences needed to break out of ‘mini-me’ hiring.

#2: Break down siloes.

Traditional hierarchal organization structures that segregate staff into departments or offices are a breeding ground for willful blindness. This is also the case for vertical siloes between different layers of seniority.

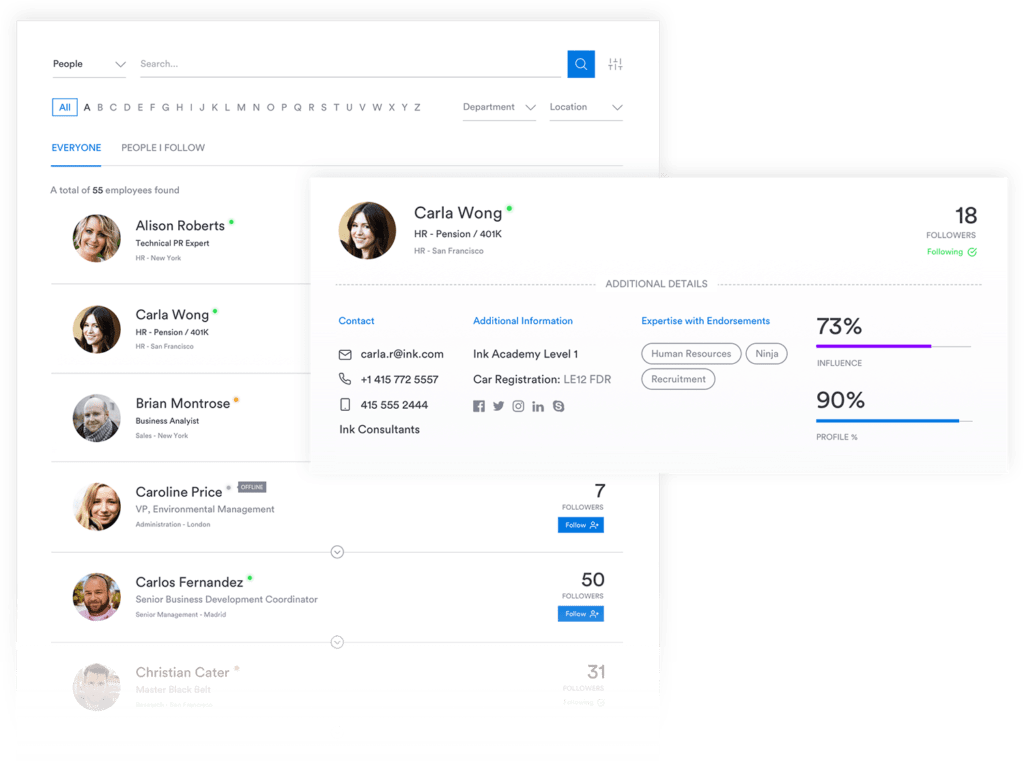

Empower staff to find one another outside of rigid structures and to collaborate across traditional barriers. This promotes the sharing of different ideas and perspectives, challenges the ‘that’s the way we’ve always done things around here’ mentality, and pushes us outside our comfort zones. This could be through inter-departmental brainstorming or idea sharing, building better connections between staff with a skill or interest-focused directory, or having a shared internal space such as an intranet.

For vertical siloes, instilling bottom-up communication routes is key. Ensure your grass-roots staff can be heard and that ideas can be escalated upwards.

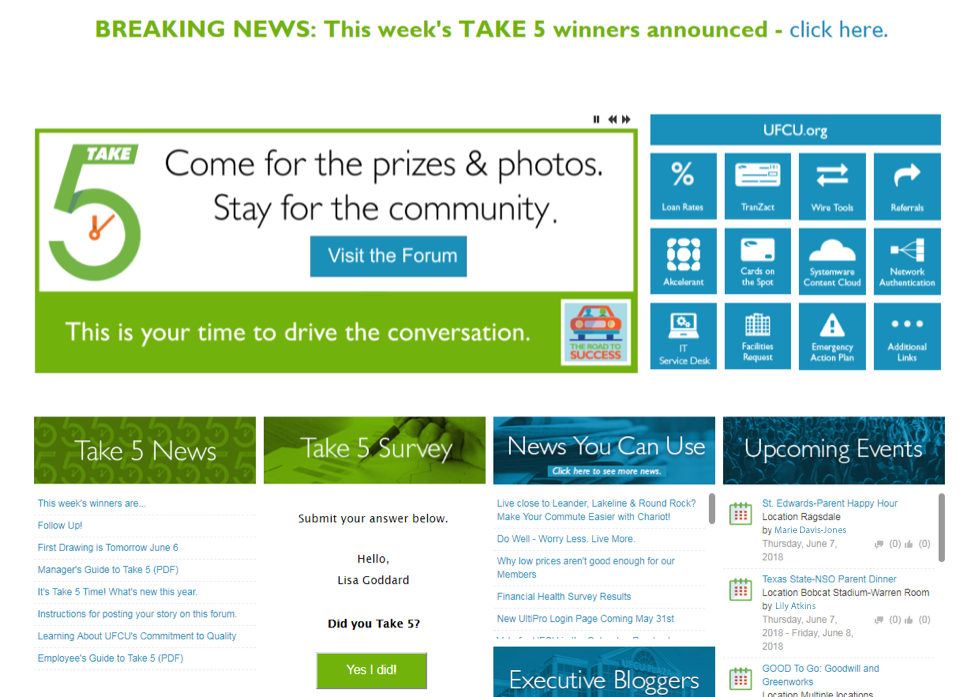

Interact customer University Federal Credit Union took this process a step further with their month-long Take 5 campaign. During the campaign, employees were encouraged to “Take 5” to speak freely with their managers in a safe environment. Forums were also used to facilitate conversation.

Publicized on the credit union’s intranet ‘Connect’, it helped to embed the organization’s culture of transparency and openness to staff feedback. Participating employees were entered to win prizes each week, including a grand price at the end of the month: reinforcing the positive behaviour.

#3: Encourage collaboration, rather than competition.

Tapping into the collective, rather than off-setting individuals against one another, is actually shown to bring greater levels of creativity, innovation and ideation.

When we pit staff against each other they are more likely to operate in siloes, be blindsighted by their own prejudices and opinions, and resist feedback which could be interpreted as a challenge. A bid to be ‘the best’ fosters blindness to faults or issues that could stand in the way. When collaborating as part of a team, staff are more receptible to different opinions and more likely to identify and problem solve issues.

#4: Use your new starters.

Sometimes, it takes a person on the outside to make us see what’s happening on the inside. Your new starters are a valuable resource in this respect. They come with a fresh perspective and different experiences: these can help shed light on those things long-termers have stopped seeing.

As part of onboarding, create a safe feedback process when new staff are encouraged to voice their initial opinions of their role and organization. Ask what processes or practices they feel could be improved, anything they feel doesn’t work well or if there are certain things in their previous experience which might benefit the organization.

#5: Share mistakes.

When something goes wrong – whether willful blindness has played a role or not – covering it up or denying it won’t solve anything. Sharing mistakes publicly among staff helps them learn from the experience, shows that mistakes are a natural and even welcome part of work – so long as we learn from them – and will encourage individuals to call out, come forward or own subsequent mistakes.

This is particularly powerful when modelled by senior leaders. There is a long-standing myth in many organizations that our leaders must be seen as god-like and flawless: models for ideal behaviour, above the human nature of making errors. This unrealistic perception not only makes it more difficult for leaders to admit fault, but creates the mindset among lower-level staff that mistakes are a sign of weakness and may prevent their ability to assume more senior roles. Next time your organization makes an error or poor judgment call, have the CEO blog about it and admit fault.

#6: Get feedback from customers or consumers.

Thanks to the surge in online review sites and the use of social media, our consumers are more empowered to speak out than ever before. However, not all organizations are listening.

It can be hard to hear that we’re failing and, in many instances, it’s understandable that we would try to explain away, excuse, or disagree with negative feedback. We may even respond appropriately by apologizing and agreeing to look into it, but if we’re being wilfully blind to a bigger problem or unwilling to accept the views or opinions of others than nothing will fundamentally change. Maintain an open mind and evaluate customer feedback carefully. What are you not seeing?

#7: Create a culture of debate and respect for ideas.

This includes publicly acknowledging and validating those who step forward to give alternative ideas or challenges things they believe to be wrong. This may be through coaching middle-managers to facilitate healthy debate in meetings, or perhaps having advocates or members of senior management respond to staff complaints, ideas or feedback: ideally publicly, for example by commenting in response to intranet forum posts.

“Once people have even one small experience of speaking up and articulating a concern and discovering that contrary to their expectation that they don’t get their heads blown off, they feel more courageous coming forward again and again and again. And when the people around them see that that’s what happens, they take courage from that and feel that they might be able to do it too.”

(Margaret Heffernan: how can we combat wilful blindness to ensure a culture of quality?)

#8: Make it personal.

The power of storytelling is widely recognized as a tool in communications, public speaking, advertising and more. It should play a critical role in the decision-making and evaluation process in your own organization.

Next time a new product, initiative or process is rolled out, don’t default to impersonal numbers or facts: zone in on the individual human story to open eyes to the true impact.

For example, perhaps disappointing sales mean you’re going to de-commission a particular product line and focus on alternatives. How will this impact front-line workers on that production line? What about the consumer who uses that product and will now no longer be able to access support or updates? Looking at the stories opens our eyes to consequences and impact, giving us all the facts.

#9: Use multiple tools, channels and processes to give staff a voice.

While some staff will feel comfortable sitting down and having a frank discussion with their line manager when they want to raise a concern, this isn’t the case for everyone. Empowering staff with different ways to speak out is a simple yet effective way to break down a culture of willful blindness.

‘Trolling’ has given anonymous digital communication a bit of a bad reputation, but it can actually be a benefit in an organization. Staff may feel more confident contributing or speaking out from the security of a keyboard. Online discussion and idea forums, instant messaging tools, anonymous reporting processes, or even just the ability to comment or contribute digitally to the ideas of others in a safe space can all give staff a voice. Combine this with town halls, smaller group sessions, one-to-ones and other face-to-face processes to tap into as many individuals as possible.

Ultimately, as with any ingrained issue, the first step to resolution is acknowledgement.

When we recognize that we don’t tend to see those things that are potentially the most dangerous – whatever the reason for our blindness – we automatically begin to see more.

Introducing 360-degree perspectives starts with accepting that we can’t, won’t, see everything by ourselves. Surrounding ourselves with different people and adopting a willingness to change our minds can not only protect us against many dangers resulting from willful blindness: it can make us better leaders, better organizations… and better people.